Debugging and Testing

Statistical Computing, 36-350

Tuesday November 15, 2022

Last week: Modeling

- Fitting models is critical to both statistical inference and prediction

- Exploratory data analysis is a very good first step and gives you a sense of what you’re dealing with before you start modeling

- Linear regression is the most basic modeling tool of all, and one of the most ubiquitous

lm()allows you to fit a linear model by specifying a formula, in terms of column names of a given data frame- Utility functions

coef(),fitted(),residuals(),summary(),plot(),predict()are very handy and should be used over manual access tricks - Logistic regression is the natural extension of linear regression to

binary data; use

glm()withfamily="binomial"and all the same utility functions - Generalized additive models add a level of flexibility in that they

allow the predictors to have nonlinear effects; use

gam()and utility functions

Part I

Debugging basics

Bug!

The original name for glitches and unexpected defects: dates back to at least Edison in 1876, but better story from Grace Hopper in 1947:

(From Wikipedia)

Debugging: what and why?

Debugging is a the process of locating, understanding, and removing bugs from your code

Why should we care to learn about this?

- The truth: you’re going to have to debug, because you’re not perfect (none of us are!) and can’t write perfect code

- Debugging is frustrating and time-consuming, but essential

- Writing code that makes it easier to debug later is worth it, even if it takes a bit more time (lots of our design ideas support this)

- Simple things you can do to help: use lots of comments, use meaningful variable names!

Debugging: how?

Debugging is (largely) a process of differential diagnosis. Stages of debugging:

- Reproduce the error: can you make the bug reappear?

- Characterize the error: what can you see that is going wrong?

- Localize the error: where in the code does the mistake originate?

- Modify the code: did you eliminate the error? Did you add new ones?

Reproduce the bug

Step 0: make if happen again

- Can we produce it repeatedly when re-running the same code, with the same input values?

- And if we run the same code in a clean copy of R, does the same thing happen?

Characterize the bug

Step 1: figure out if it’s a pervasive/big problem

- How much can we change the inputs and get the same error?

- Or is it a different error?

- And how big is the error?

Localize the bug

Step 2: find out exactly where things are going wrong

- This is most often the hardest part!

- Understand errors, using

traceback(), and alsocat(),print() - Interactively debug with the R tool

browser()

Localizing can be easy or hard

Sometimes error messages are easier to decode, sometimes they’re harder; this can make locating the bug easier or harder

my.plotter = function(x, y, my.list=NULL) {

if (!is.null(my.list))

plot(my.list, main="A plot from my.list!")

else

plot(x, y, main="A plot from x, y!")

}my.plotter(my.list=list(x=-10:10, y=(-10:10)^3))my.plotter() # Easy to understand error message## Error in plot(x, y, main = "A plot from x, y!"): argument "x" is missing, with no defaultmy.plotter(my.list=list(x=-10:10, Y=(-10:10)^3)) # Not as clear## Error in xy.coords(x, y, xlabel, ylabel, log): 'x' is a list, but does not have components 'x' and 'y'Who called xy.coords()? (Not us, at least not

explicitly!) And why is it saying ‘x’ is a list? (We never set it to be

so!)

traceback()

Calling traceback(), after an error: traces back through

all the function calls leading to the error

- Start your attention at the “bottom”, where you recognize the function you called

- Read your way up to the “top”, which is the lowest-level function that produces the error

- Often the most useful bit is somewhere in the middle

If you run

my.plotter(my.list=list(x=-10:10, Y=(-10:10)^3)) in the

console, then call traceback(), you’ll see:

> traceback()

5: stop("'x' is a list, but does not have components 'x' and 'y'")

4: xy.coords(x, y, xlabel, ylabel, log)

3: plot.default(my.list, main = "A plot from my.list!")

2: plot(my.list, main = "A plot from my.list!") at #2

1: my.plotter(my.list = list(x = -10:10, Y = (-10:10)^3))We can see that my.plotter() is calling

plot() is calling plot.default() is calling

xy.coords(), and this last function is throwing the

error

Why? Its first argument x is being set to

my.list, which is OK, but then it’s expecting this list to

have components named x and y (ours are named

x and Y)

Part II

Debugging tools

cat(), print()

Most primitive strategy: manually call cat() or

print() at various points, to print out the state of

variables, to help you localize the error

This is the “stone knives and bear skins” approach to debugging; it is still very popular among some people (actual quote from stackoverflow):

I’ve been a software developer for over twenty years … I’ve never had a problem I could not debug using some careful thought, and well-placed debugging print statements. Many people say that my techniques are primitive, and using a real debugger in an IDE is much better. Yet from my observation, IDE users don’t appear to debug faster or more successfully than I can, using my stone knives and bear skins.

Specialized tools for debugging

R provides you with many debugging tools. Why should we use them, and

move past our handy cat() or print()

statements?

Let’s see what our primitive hunter found on stackoverflow, after a receiving bunch of suggestions in response to his quote:

Sweet! … Very illuminating. Debuggers can help me do ad hoc inspection or alteration of variables, code, or any other aspect of the runtime environment, whereas manual debugging requires me to stop, edit, and re-execute.

browser()

One of the simplest but most powerful built-in debugging tools:

browser(). Place a call to browser() at any

point in your function that you want to debug. As in:

my.fun = function(arg1, arg2, arg3) {

# Some initial code

browser()

# Some final code

}Then redefine the function in the console, and run it. Once execution

gets to the line with browser(), you’ll enter an

interactive debug mode

Things to do while browsing

While in the interactive debug mode granted to you by

browser(), you can type any normal R code into the console,

to be executed within in the function environment, so you can, e.g.,

investigate the values of variables defined in the function

You can also type:

- “n” (or simply return) to execute the next command

- “s” to step into the next function

- “f” to finish the current loop or function

- “c” to continue execution normally

- “Q” to stop the function and return to the console

(To print any variables named n, s,

f, c, or Q, defined in the

function environment, use print(n), print(s),

etc.)

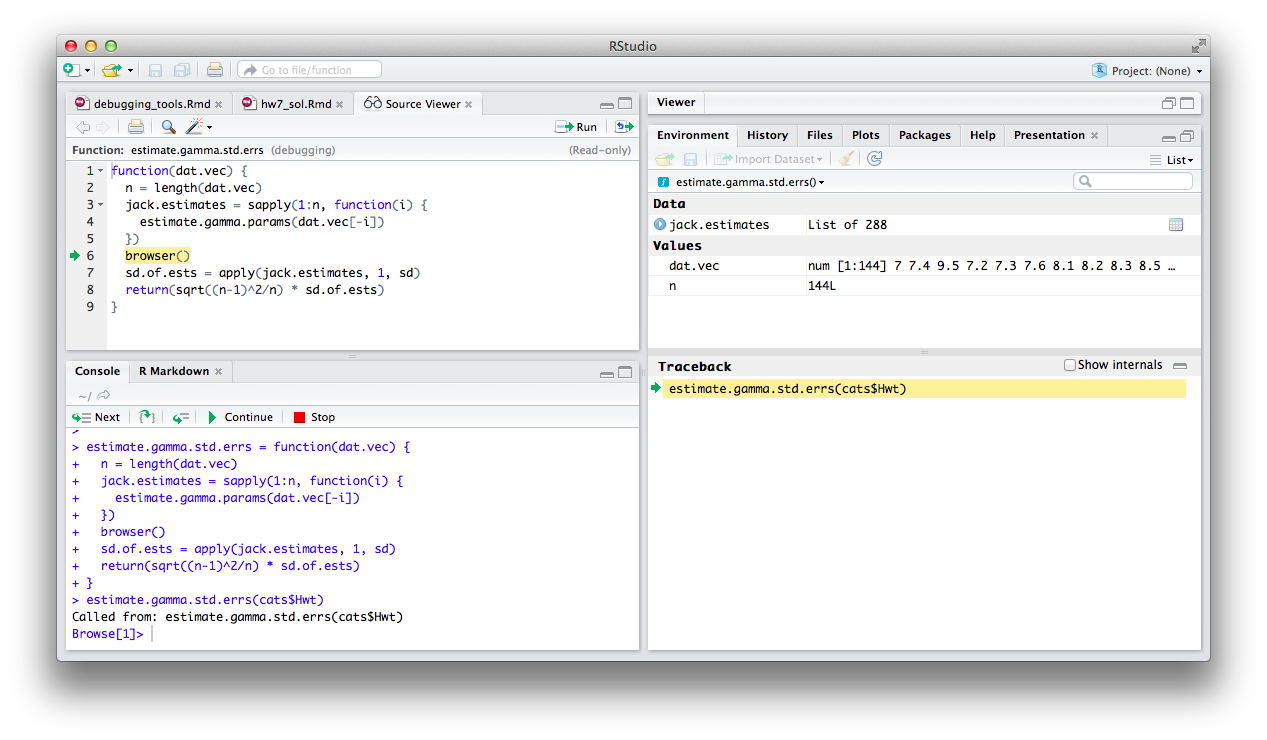

Browsing in R Studio

You have buttons to click that do the same thing as “n”, “s”, “f”, “c”, “Q” in the “Console” panel; you can see the locally defined variables in the “Environment” panel; the traceback in the “Traceback” panel

Knitting and debugging

As with cat(), print(),

traceback(), used for debugging, you should only run

browser() in the console, never in an Rmd code chunk that

is supposed to be evaluated when knitting

But, to keep track of your debugging code (that you’ll run in the

console), you can still use code chunks in Rmd, you just have to specify

eval=FALSE

# As an example, here's a code chunk that we can keep around in this Rmd doc,

# but that will never be evaluated (because eval=FALSE) in the Rmd file, take

# a look at it!

big.mat = matrix(rnorm(1000)^3, 1000, 1000)

big.mat

# Note that the output of big.mat is not printed to the console, and also

# that big.mat was never actually created! (This code was not evaluated)Part III

Testing

What is testing?

Testing is the systematic writing of additional code to ensure your functions behave properly. We’ll focus on two aspects

- Assertions: checking your function is being passed in proper inputs

- Unit tests: checking your function does the right thing in basic cases

Benefits of testing:

- Enables you to catch problems early (easier debugging)

- Provides natural documentation of your functions

- Encourages you to write simpler functions via refactoring

Of course, this requires you to spend more time upfront, but it is often worth it (saves time spent debugging later)

Assertions

Assertions are checks to ensure that the inputs to your function are properly formatted

- For example, if your function expects a matrix, then we first check that it is actually a matrix (and not a vector, say)

- Otherwise your function could be acting on unexpected input types, and bugs could arise that are hard to interpret/locate

- So an assertion stops the execution of the function as soon as it encounters an unexpected input

# Function to create n x n matrix of 0s

create.matrix.simple = function(n){

matrix(0, n, n)

}

# Not meaningful errors!

create.matrix.simple(4)## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 0 0 0 0

## [2,] 0 0 0 0

## [3,] 0 0 0 0

## [4,] 0 0 0 0create.matrix.simple(4.1)## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 0 0 0 0

## [2,] 0 0 0 0

## [3,] 0 0 0 0

## [4,] 0 0 0 0create.matrix.simple("asdf")## Error in matrix(0, n, n): non-numeric matrix extentassert_that()

We’ll be using assert_that() function in the

assertthat package to make assertions: allows us to write

custom, meaningful error messages

library(assertthat)

create.matrix = function(n){

assert_that(length(n) == 1 && is.numeric(n) &&

n > 0 && n %% 1 == 0,

msg="n is not a positive integer")

matrix(0, n, n)

}

# Errors are now meaningful

create.matrix(4)## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 0 0 0 0

## [2,] 0 0 0 0

## [3,] 0 0 0 0

## [4,] 0 0 0 0create.matrix(4.1)## Error: n is not a positive integercreate.matrix("asdf")## Error: n is not a positive integerAnother example

# Function that performs linear regression

run.lm.simple = function(dat){

res = lm(X1 ~ ., data = dat)

coef(res)

}

mat = matrix(rnorm(20), 10, 2)

colnames(mat) = paste0("X", 1:2)

dat = as.data.frame(mat)

# Not meaningful errors

run.lm.simple(dat)## (Intercept) X2

## 0.09957273 0.21538540run.lm.simple(mat)## Error in model.frame.default(formula = X1 ~ ., data = dat, drop.unused.levels = TRUE): 'data' must be a data.frame, not a matrix or an array# Meaningful errors

run.lm = function(dat){

assert_that(is.data.frame(dat),

msg="dat must be a data frame")

res = lm(X1 ~ ., data = dat)

coef(res)

}

run.lm(dat)## (Intercept) X2

## 0.09957273 0.21538540run.lm(mat)## Error: dat must be a data frameUnit tests

Unit tests are used to check that your code passes basic sanity

checks at various stages of development. We’ll be using

test_that() function in the testthat package

to do unit tests: you’ll learn the details in lab

Some high-level tips:

- Always run your unit tests whenever you change your function

- Also always run unit tests before expensive computations

- When you encounter a bug during your code development, add an appropriate unit test

- Write short functions. It’s hard to write a unit test for a 100+ line function

Summary

- Debugging involves diagnosing your code when you encounter an error

or unexpected behavior

- Step 0: Reproduce the error

- Step 1: Characterize the error

- Step 2: Localize the error

- Step 3: Modify the code

traceback(),cat(),print(): manual debugging toolsbrowser(): interactive debugging tool- Testing involves writing additional code to ensure your functions behave as expected

- Compared to debugging, it is proactive, rather than reactive

assert_that(),test_that(): tools for assertions and unit tests- Important: it’s hard to teach good coding practices. The best way to learn is to implement these yourself from now onwards!